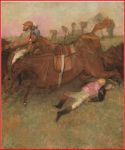

National Gallery of Art Gallery 83 Vincent Van Gogh Self Portrait

Click on the Palette To See UP CLOSE the Texture in the Paint Swatches

Click on the Detail To Study the Face Strokes & Color UP CLOSE

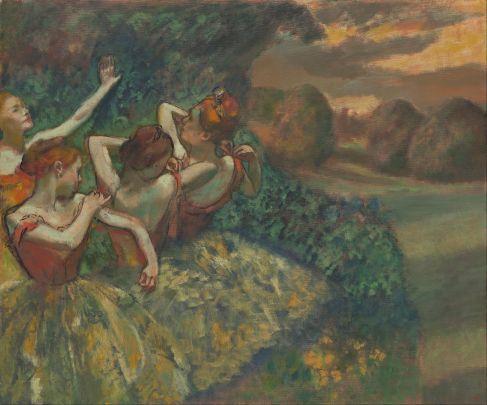

Before you visit the National Gallery of Art, go to the website and search for your favorite artist. Find where his/her art is exhibited; and go there first. Vincent Van Gogh and Matisse are probably my two favorite artists; yet, Van Gogh must trump Matisse because I searched for him first. [Incidentally, at the time of this writing, the Matisse exhibit is not open]. Van Gogh is in Gallery 83. Fortunately, that is where I launched my first visit to the National Gallery of Art. It will require several days to tour all of the galleries at NGA.

After having seen art only in books for many, many years, I was almost afraid to see the actual paintings. I was afraid that the work would not be as magnificent as I had imagined it to be; yet, that is not at all the case with Van Gogh’s work. His art is even more magnificent first hand. I knew that Van Gogh’s art is highly textured–thick, swirly, etc.; but I did not realize how brilliantly lit and colored much of his work is. That is particularly true of this self-portrait, painted in the characteristic Van Gogh, delft blue and its complementary yellows and oranges. The brilliance is also apparent in La Mousme, which I will discuss in another post.

Following is what the NGA site has to say about Van Gogh’s self portrait:

“The National Gallery’s self-portrait, painted at the asylum at St.-Rémy, where Van Gogh had committed himself following a mental breakdown, is among the last self-portraits he made. During his stay he suffered another collapse and remained confined in his room for more than a month, not even venturing into the garden. Once he was able to paint again, this was the first canvas he made, apparently in a single sitting. Van Gogh believed strongly that only work could restore his health. Here, as he had in two earlier self-portraits, he holds the tools that mark his identity as a painter, a palette and brushes, and he wears a painter’s smock. In his short career Van Gogh made almost 2,000 paintings and drawings and wrote more than 800 letters, most to his brother Théo, chronicling his aims and struggles as an artist. He worked long and very deliberately to perfect his art.

“The fervor and fragility of Van Gogh’s life are told on this canvas by stark contrasts of color and restless brushstrokes. Heavy lines of paint seem to emanate from his head like a wavering force field, energized by his own intensity. This background sets off the complementary colors of his green-tinged face and orange hair, keying his image to a higher pitch. “I was thin and pale as a ghost,” Van Gogh wrote as he described this portrait to Théo. “It is dark violet blue and the head whitish with yellow hair, so it has a color effect.”

“Van Gogh worked on a second self-portrait at about the same time. Although its background is animated with swirling brushstrokes, the more muted color scheme lends the image a calmer aspect. The artist believed, however, that the painting seen here captured his “true character.”

- Gogh, Vincent van (painter)

- Dutch, 1853 – 1890

- Self-Portrait

- 1889

- oil on canvas

- overall: 57.79 × 44.5 cm (22 3/4 × 17 1/2 in.)

- framed: 82.9 x 69.2 x 6.7 cm (32 5/8 x 27 1/4 x 2 5/8 in.)

- Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney

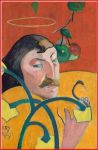

- “Vincent van Gogh is instantly recognizable by his reddish hair and beard, his gaunt features, and intense gaze Van Gogh painted some thirty-six self-portraits in the space of only ten years. Perhaps only Rembrandt produced more images of himself, and that in a career that spanned decades. For many artists, like Rembrandt and Van Gogh, the self-portrait was a critical exploration of personal realization and aesthetic achievement.

- The NGA only has one of Van Gogh’s Self Portraits. Here are others:

-

Vincent van Gogh grew up in the southern Netherlands, where his father was a minister. After seven years at a commercial art firm, Van Gogh’s desire to help humanity led him to become a teacher, preacher, and missionary—yet without success. Working as a missionary among coal miners in Belgium, he had begun to draw in earnest; finally, dismissed by church authorities in 1880, he found his vocation in art.

Van Gogh’s earliest paintings were earth-toned scenes of nature and peasants, but he became increasingly influenced by Japanese prints and the work of the impressionists in France. In 1886 he arrived in Paris, where his real formation as a painter began. Under the influence of Camille Pissarro, Van Gogh brightened his somber palette and juxtaposed complementary colors for luminous effect. Younger artists like Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Gauguin prompted him to use color symbolically and for its emotional resonance.

Although stimulated by the city’s artistic environment, Van Gogh found life in Paris physically exhausting and moved in early 1888 to Arles. He hoped Provence’s warm climate would relax him and that the brilliant colors and strong light of the south would provide inspiration for his art. Working feverishly, Van Gogh pushed his style to greater expression with intense, energetic brushwork and saturated, complementary colors. Yet, his densely painted canvases remained connected to nature—their colors and rhythmic surfaces communicate the spiritual power he believed inhabited and shaped nature’s forms. His activity undisciplined; quite the opposite, he worked diligently to perfect his craft.

Van Gogh hoped to attract like-minded painters to Arles, but only Gauguin joined him, staying about two months. It was soon clear that their personalities and artistic temperaments were incompatible, and Van Gogh suffered a breakdown just before Christmas. In April, following periods of intense work interrupted by recurring mental disturbances, Van Gogh committed himself to a sanitarium in St.-Rémy. He painted whenever he could, believing that in work lay his only chance for sanity. After a year, he returned north to be closer to his brother Théo, who had been his constant support; in July he died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.”http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/exhibitions/1998/vangogh.html

Also see: http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/exhibitions/1998/vangogh.html