From the moment the American Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) made her debut in 1879 with the group of artists known as the impressionists, her name has been linked with that of the Frenchman Edgar Degas (1834–1917). Cassatt stated that her first encounter with Degas’s art “changed my life,” while Degas, upon seeing Cassatt’s art for the first time, reputedly remarked, “there is someone who feels as I do.” It was this shared sensibility as much as Cassatt’s extraordinary talent that drew Degas’s attention.

The affinity between the two artists is undeniable. Both were realists who drew their inspiration from the human figure and the depiction of modern life, while they eschewed landscape almost entirely.

Both were highly educated, known for their intelligence and wit, and from well-to-do banking families. They were peers, moving in the same social and intellectual circles. Cassatt, who had settled in Paris in 1874, first met Degas in 1877 when he invited her to participate with the impressionists at their next exhibition. Over the next decade, the two artists engaged in an intense dialogue, turning to each other for advice and challenging each other to experiment with materials and techniques. Both made printmaking an important aspect of their careers and for a time collaborated on their endeavors. Their admiration and support for each other endured long after their art began to head in different directions: Degas continued to acquire Cassatt’s work, while she promoted his to collectors back in the United States. They remained devoted friends for forty years, until Degas’s death.

Infrared reflectogram composite with Cassatt’s original demarcation (solid line), Degas’s alteration (broken line), and the dog’s alternative placement (circle)

“Little Girl in a Blue Armchair”: A Closer Look

In a letter to the French art dealer Ambroise Vollard, Cassatt wrote that Degas not only advised her as she painted Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, but even worked on the background. Recent

cleaning, restoration, and technical

analysis have been instrumental in

identifying Degas’s role. The paint

surface in the corner of the room

beyond the furniture shows evidence

of having been scraped or rubbed, a

technique used often by Degas but

only rarely by Cassatt. Infrared imaging,

moreover, reveals that Cassatt had initially used a horizontal line to mark the edge of the floor and a single back wall that was parallel to the picture plane. Degas made the space more dynamic by adding the corner, creating a junction of two walls and thus introducing a diagonal that expanded the room spatially. The use of such wide angle diagonals to define interior architecture was common in Degas’s work, but unprecedented in Cassatt’s.

To accommodate the new corner, Cassatt had to adjust her composition. She repositioned the armless couch in the background to align with the now sloping wall. She also reconsidered the placement of the dog. While it now rests comfortably on a chair, the infrared image indicates that she had tried placing it on the floor, seated in front of the couch. Eventually, she painted it out there and set it back on the chair.

Mary Cassatt at the Louvre

Degas’s own planned contribution for the failed journal Le Jour et la nuit was the etching now known asMary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery. Cassatt once remarked that she posed for Degas “only once in a while when he finds the movement difficult and the model cannot seem to get his idea.” Yet the theme of Cassatt strolling through the Louvre clearly fascinated him, resulting in a rich body of work produced in a range of media over a number of years. Encompassing two prints, at least five drawings, a half-dozen pastels, and two paintings, the series marks one of Degas’s most intense and sustained meditations upon a single motif.

Beyond 1886

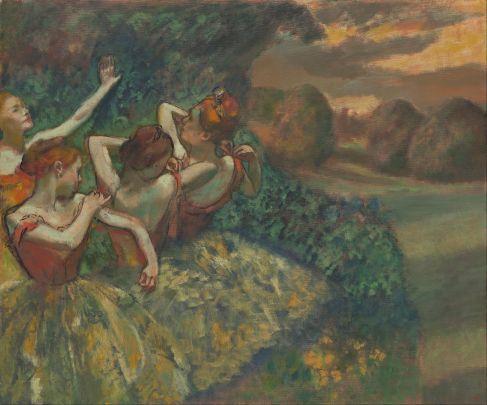

The final impressionist exhibition in 1886 marked a turning point in Degas and Cassatt’s relationship. Although their friendship endured until his death, their interactions noticeably diminished as they began to move in different directions. Cassatt focused increasingly on depictions of mothers and children. The once energetic brushwork of her earlier impressionist paintings gave way to greater precision, and she developed a proclivity for bold colors and elaborate patterns. Degas’s art underwent a radical stylistic transformation as well. His compositions became increasingly simplified, his colors more vibrant, his paint handling broader and more expressive. He also devoted much of his energy to reworking earlier canvasses.

Degas – Woman Viewed from Behind c. 1879 – 1885

Degas’s choice of the Louvre as the setting for this group of works spoke to the two friends’ mutual appreciation for art and its tradition. In the series, he depicted Cassatt as an elegantly dressed museum goer, wholly absorbed in her study of art. Nearby, a seated companion (usually identified as Cassatt’s sister Lydia) looks up from her guidebook. Cassatt, with her back turned fully to the viewer, balances against an umbrella in a pose that highlights the curve of her body and underscores her air of assurance. Although the precise relationship between the various works is not entirely certain, Degas most likely began with drawings and pastels of individual figures that served as references for the series as a whole. The more elaborate pastels and paintings of women visiting a museum culminate the series

The previous information is from: http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/features/degas-cassatt.html